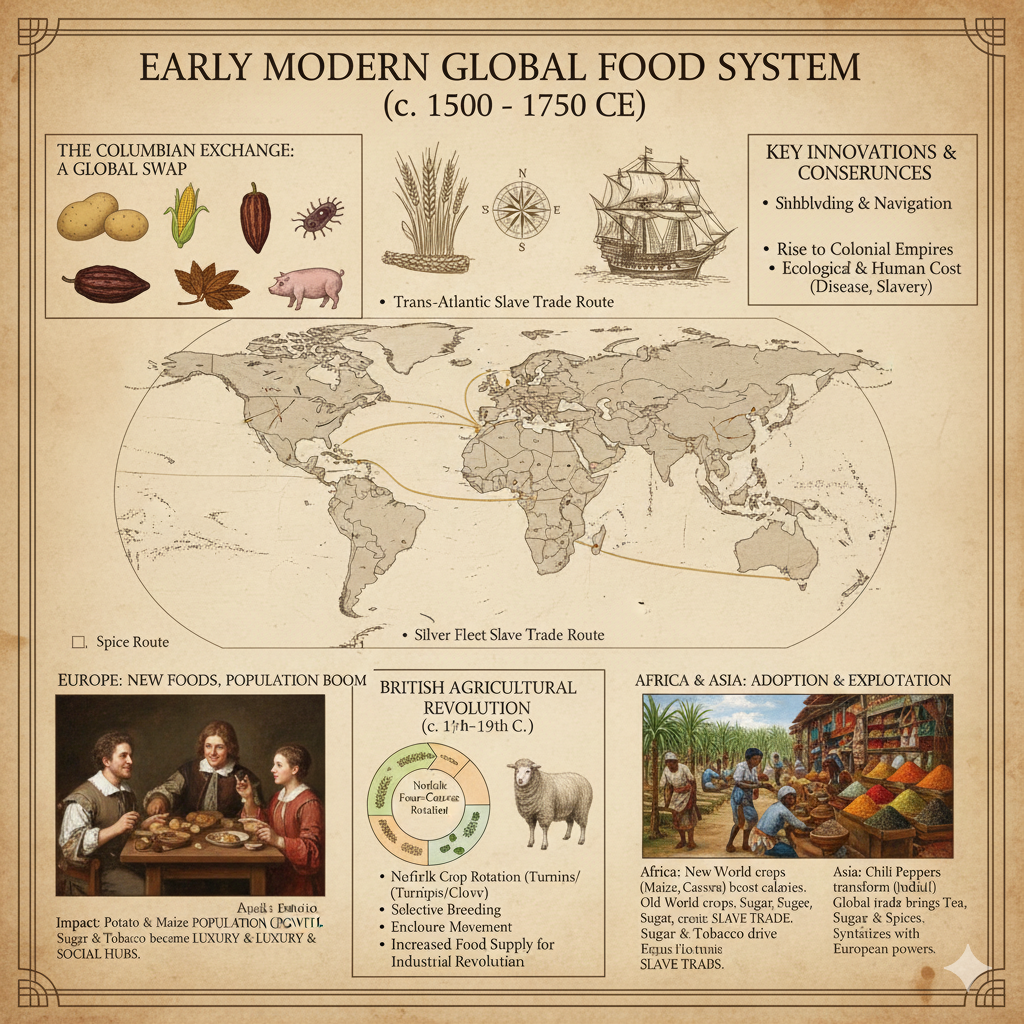

The Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations (including slaves), technology, diseases, and ideas between the American continents (New World) and the Old World (Europe, Africa, and Asia) in the 15th and 16th centuries, following Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage.

The staple crops of potatoes, maize (corn), and cassava were arguably the most important transfers. They were high-calorie, nutritious, and could grow in diverse climates, helping to prevent famine in Europe, Africa, and China. Tomatoes, peppers (including chili peppers), squash, and pumpkins became integrated into nearly every global cuisine. Cash Crops: Tobacco and cacao (the source of chocolate) became highly valuable commodities that drove early global trade.

The lack of large domesticated animals in the Americas meant the Old World animals were quickly adopted and transformed the landscape. Cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, and goats were introduced. Horses revolutionized transportation, warfare, and hunting for Native American tribes, particularly on the Great Plains. Pigs and cattle became crucial new protein sources. European settlers introduced their staple foods to sustain their colonies such as wheat, barley, rye, and rice (including African varieties, often brought by enslaved people).

The vast flow of new commodities and precious metals (like silver) from the Americas powered the rise of European mercantilism and early global capitalism. But Native American populations declined by 50% to 90% due to diseases to which they had no resistance, profoundly destabilizing societies and clearing the way for European colonization. The massive death toll among Native American populations created a severe labour shortage for the newly established plantations (especially sugar, cotton, and tobacco). This demand directly fueled the Transatlantic Slave Trade, forcibly bringing millions of Africans to the Americas.

In Britain, Although initially met with suspicion, the potato was introduced to Britain in the late 16th century (often associated with explorers like Sir Walter Raleigh). Over the next two centuries, the potato became a crucial staple for the working class, particularly in Ireland and parts of Scotland. It offered significantly more calories and vitamins per acre than wheat or barley, providing a vital source of cheap energy that helped support a growing population and stave off famine. The new American crops (especially the potato) allowed British farming to be far more productive, raising the floor for the poorest citizens and reducing reliance on expensive wheat and meat. Maize was used principally as animal fodder.

The tomato arrived in Britain in the mid-16th century. Like the potato, it was initially viewed with great suspicion, largely because it belongs to the deadly nightshade family. It was first grown as an ornamental plant. It wasn’t until the 18th century that it was widely accepted for consumption, after which it became indispensable to British and European cuisine.

Chocolate was introduced to the elite classes in the 17th century, first as a bitter beverage and later as a sweetened drink. It grew from an aristocratic novelty to a popular indulgence. Introduced quickly, tobacco use exploded, becoming a massive cash crop and a staple of colonial trade that fundamentally changed social habits.

The Second Agricultural Revolution

The adoption of New World crops, particularly the high-calorie potato, increased overall land productivity and provided a cheap, resilient food source for the growing working class. A rapidly increasing British population (especially in cities due to early of industrialisation) created an enormous and urgent market demand for cheap, reliable food, driving farmers to maximize their productivity.

It was one of the drivers of the British Agricultural Revolution between the 17th and 19th centuries, when the application of science, technology, and economic principles to increase food production efficiency, provided the foundation for the Industrial Revolution. A series of Parliamentary acts consolidated scattered, communal land into large, private, fenced fields (enclosures). This stripped small farmers of their common rights but incentivised large landowners to experiment and invest heavily in the new, profitable farming methods.

The most important change was the replacement of the medieval fallow year with fodder crops. Under the Norfolk Four-Course Rotation system, the rotation was: 1) Wheat (cash crop); 2) Turnips (winter feed for livestock); 3) Barley (cash crop); 4) Clover/Grass (nitrogen-fixer and summer feed) This innovation eliminated wasted land, restored soil fertility (via clover), and allowed farmers to keep more livestock through the winter. Inventions like Jethro Tull’s seed drill (1701) helped plant seeds in neat rows, reducing waste and increasing efficiency.

Alongside this, figures like Robert Bakewell pioneered selective breeding as a scientific practice, deliberately mating animals with desirable traits (e.g., larger sheep, heavier cattle) to increase the size and yield of livestock.

Countries like France, Germany, and the Netherlands began adopting similar systems in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but it was slowed because land was still held under communal or feudal arrangements well into the 19th century. German states were particularly advanced in applying chemistry to farming, pioneering early forms of chemical fertilizers in the 19th century. The United States and Canada adopted the principles quickly, especially after the mid-19th century. The US had vast, open land, making the large-scale, mechanized farming principles of the revolution (which eventually led to inventions like the reaper) essential and highly effective. They adapted New World crops (like corn) into efficient rotations.

The Industrial Revolution

These changes, combined with mass migration to the cities, where the urban masses could not grow their own food, had the effect of decoupling the majority of the population from food production.

While food became more available, the diet of the urban working class became monotonous and often deficient. The diet of the urban poor centered on three cheap staples: bread, tea, and potatoes. Potatoes: werethe cheapest, most energy-dense food source, crucial for feeding large families. Tea became a ubiquitous and cheap beverage, consumed constantly, often heavily sweetened with imported sugar (a product of the global colonial system and slave labour).

Traditional garden vegetables and foraged foods disappeared from the urban diet. The consumption of meat dropped significantly for the poor, as high-quality cuts were expensive. The monotonous, heavily carbohydrate-based diet, low in protein and fresh vitamins, led to widespread malnutrition diseases like rickets (vitamin D deficiency) and scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) among the factory workers.

The mass production of cheap food for profit led to rampant food fraud, and adulteration, creating a public health crisis.

The Industrial Revolution provided the technology to move food faster and preserve it longer. Steam engines, canals, railways, and eventually steamships, allowed food to be moved vast distances. Britain began importing large quantities of cheap American grain, particularly after the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The invention of canning in the early 19th century (originally to feed Napoleon’s army) allowed meat, vegetables, and fruit to be preserved for long periods, which was essential for feeding the Navy, the Army, and later, the urban populace. While fully effective mechanical refrigeration arrived later in the 19th century, earlier experiments paved the way for the import of fresh meat from Australia and South America, completely changing the meat supply chain by the 1880s.

Companies began placing their names (brands) on packages as a promise of consistent quality and safety. This practice—pioneered by companies like H.J. Heinz (“57 Varieties”) and Quaker Oats—allowed consumers to select a trusted product without having to inspect it themselves. The brand became a crucial marketing tool for building consumer confidence. The proliferation of cheap, mass-produced newspapers and magazines in the late 19th century allowed food manufacturers to use national advertising campaigns to build brand recognition, often appealing directly to housewives with promises of convenience, purity, and scientific nutrition.

Gemini AI helped me with this. Its sources include: