Facebook post #059 (Mar 2021)

1789. La Trinneté, Jèrri (Jersey). A baby girl is born to a father yearning for his own piece of land. He was my 5th gt-grandfather, Moïse Picot: she was named Susanne. A few years later, Susanne watched her father look over that new piece of land, by First Tower, a mile or so from Saint Hélyi town.

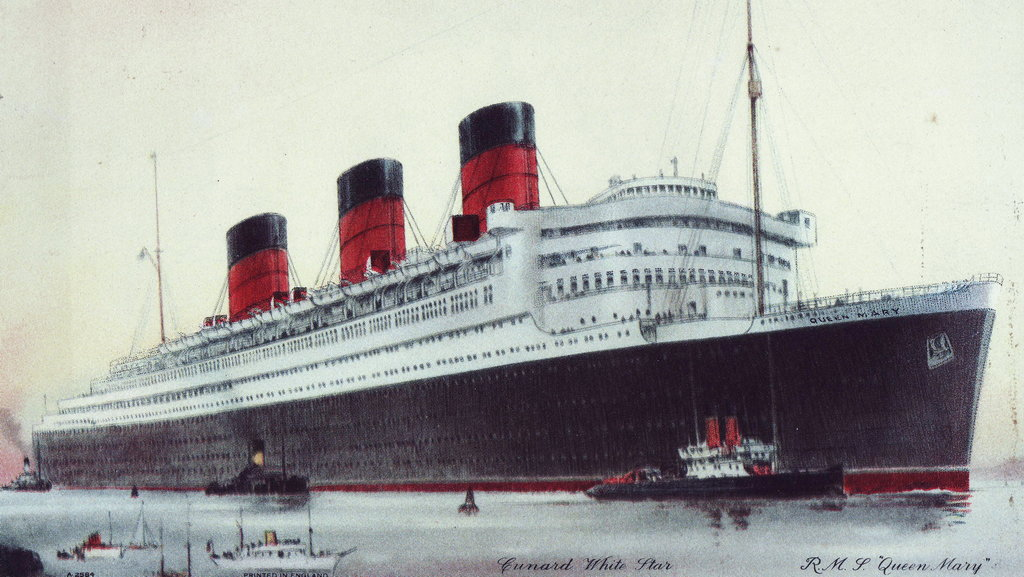

The No. 1 Martello tower had been built ten years earlier to defend St Helier against the French. It hadn’t worked – the French had grown impatient of Jersey pirates threatening the American Revolution. On Old Christmas Day, 6 January 1781, using renegade intelligence, they sailed 30 small boats across the 12 miles of sea into a narrow channel on the SE corner of the island. One or two thousand troops marched the ten miles to town, and took command. The governor ordered surrender, but the English garrison fought on and drove out the invaders. This was the last attempt by France to control the island, (which has also never been part of England, Britain, the UK or the EU).

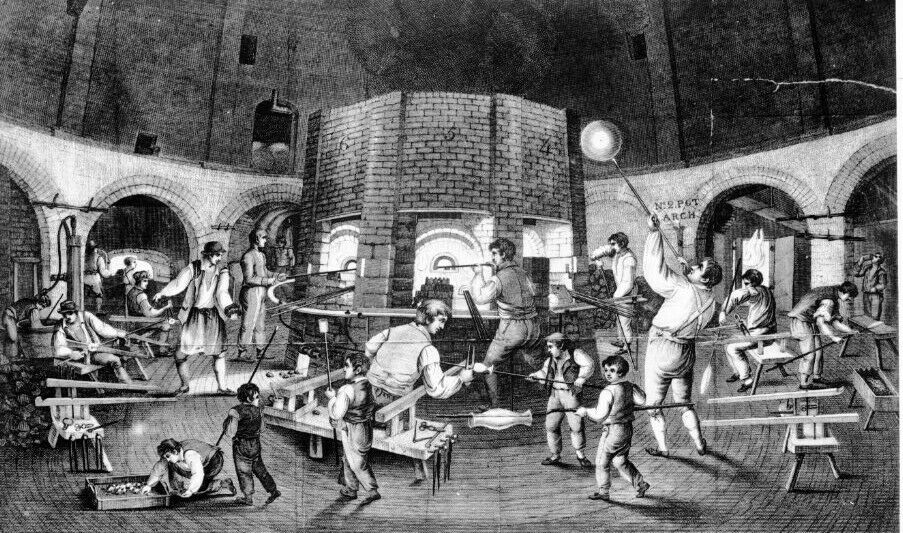

At First Tower, Moïse almost wept at the immensity of the task ahead of him in converting sand dunes into productive land. But he set to work. They lived in Almon Cottage (pic) which stayed in the family until the 1990s. The community was scattered, and nothing could be taken for granted. Bread was made at home, a task which fell to young Susanne. Soon she was making extra, and hawking it around the fishermen’s cottages. In 1808, she married Pierre Le Brun, a shoemaker.

Since the French débâcle, French names had been going out of fashion, and later records have the couple as Peter and Susan. (This never applied universally, and most street names in town are given in two languages to this day – but the alternative names are not usually synonyms. About two thirds of the population identify as native Jèrriais, but only about 3% speak the language.)

Susanne Picot

Susan kept baking, and formally set up in business in 1824, immediately opposite First Tower. This was also the year that Susan gave birth to the fifth of her eight children. By the 1851 census, her eldest son, also Pierre/Peter, had taken over the shoemaking from his father, and her husband had joined her in the bakery business. Like many Jèrriais, Peter Jr. spent time at sea, but when his father died, he took over the bakery.

When I visited Jersey in 1997, the first thing I saw as I drove off the ferry was an enormous Mother’s Pride bakery. However, the Le Brun Bakehouse was still there on the corner opposite First Tower. It was now a café, and we enjoyed cake baked on the premises. Even better, the Old Bakehouse (pic) was still in the family.

Peter’s son Moses was born in 1859, and by 1871 he was part of the business. His older brother was a carpenter nearby, with his widowed mother being the head of the household. Later in the decade, Moses had the good fortune to meet a woman as formidable as his grandmother: Esther Elizabeth De Gruchy.

In 1880, they married on Portsea Island, Hampshire (more on this anon). Esther joined the business, and became its driving force, alongside – needless to say – bringing up four young children. In 1881, they employed two men and a boy. They worked hard to develop the business and it remained the island’s main bakery.

Sadly, Moses took to drink; he was dead within six years, leaving Esther a widow at age 28. With fortitude, she continued looking after the business and its employees and the four children. In time, her son Jack helped out. The business remained prosperous, and they were able to keep a servant to help out domestically. My Mum’s second cousin, Antoinette Herivel, posted online a lovely hand-coloured photo of the children from about 1892.

Esther was sometimes taken as a companion by her sister-in-law on trips to Europe, especially Germany, a popular destination at the time. They even named their house after Waldeck, a German county. It feels like a long way from 1789 – but also from 1914.

The business apparently continued through WWI, and Jack took over the business when his mother died in 1922. His wife apparently made all her own clothes and loved to gossip in Jèrriais. His brother went into shipping, and became learned in Jersey history. One sister married a man in a similar line and emigrated to Australia. More on younger sister Elsie soon.

The main bakery business was purchased in 1938 by Ralph Le Marquand, brother of a Jersey Senator. Then, from 30 June 1940, Jersey was occupied by Nazi Germany (see post 12). The initial shock was mitigated by a polite and professional occupying force operating via the local government.

As the war progressed, life became progressively harsher and morale declined. The population became aware of forced labour on the new fortifications and sinister underground ‘hospital’. The family told me of harsh punishments if radios were discovered and the fear involved in undeclared flour milling. The winter of 1944-45 was very cold and the population was on the point of starvation. Relief from the Red Cross, and liberation on 9 May 1945, could not have come soon enough.

The bakery was expanded after WWII, and moved locally, and then moved again in the 1980s from the residential area to an industrial estate. However, it had lost its leading position – a traditional baker unable to compete with modern food processing and ‘loss leading’ by the supermarkets. It changed hands in 2007 and was renamed, and finally closed in 2013.