Facebook post #047 (Dec 2020; updated Oct 2025)

So, we left 3rd gt-grandparents Charles and Maria Brittain in 1851, he a silver plater. But in the 1861, 1871 and 1881 censuses, they lived on the other side of the Jewellery Quarter, and – somehow – had become chaplain to the workhouse and the asylum!

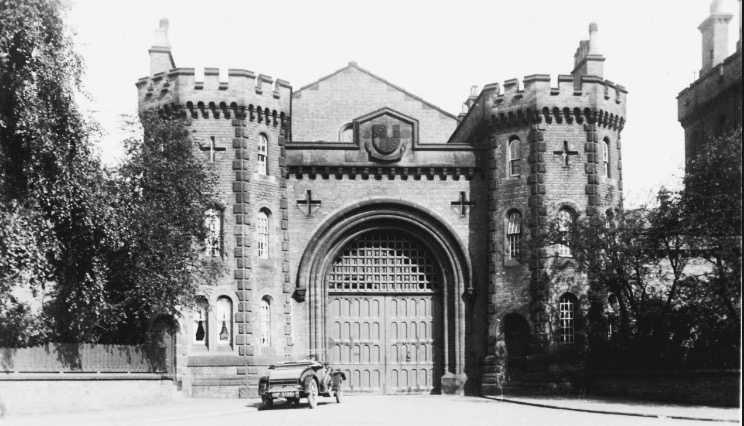

The asylum had opened in 1850, and would close, as All Saints Hospital hospital, in 2000; all but the entrance block was demolished. The remainder of the site was used to expand Winson Green Prison (now HMP Birmingham), where David Meaden was governor (post 45).

Thirty years after it opened, another was built down the road at Rubery. It was here that our unfortunate Samuel Wheaver ended his days in shell shock (post 42).

The relationship between the various buildings has been quite confusing in some accounts, so a map is called for. Top left is the prison, and immediately to its East, the ‘Borough Lunatic Asylum’, with Lodge Road, running across the top.

Below these complexes is the ‘old line’ of the Birmingham Canal, latterly known as the Soho Loop (Soho having a special place in the country’s industrial history). The Asylum Bridge across the canal must have been well-known to Charles. The walled area was the Winson Green Corporation Yard Wharf; gas works and isolation hospitals are also shown.

But the area is dominated by the Birmingham Union Workhouse, which opened in 1852 – quite new when Charles took up his job. It could accommodate 700 adults and 300 children.

The fear of ending up in the workhouse would have been palpable; our unfortunate Benjamin Weaver (whose descendant married Charles’s) ended his days down the road in the Aston Union Workhouse in 1881 (post 24).

The large infirmary to the West opened in 1888 – after Charles’ time – to a design championed by Florence Nightingale. She had overseen the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse system: their predecessors were caricatured by Dickens in ‘Mrs Gamp’.

The infirmary eventually became City Hospital, and swallowed up the workhouse. Most of the site was cleared by the 1990s, but the entrance block, with its ‘arch of tears’, survived until 2017. The hospital itself closed in 2024 (after the original version of this post was written).

Charles and Maria had 14 children, and the church dominated their lives. They sent two of their daughters to the Clergy Daughters School – it had moved to Westmorland since the time two of the Brontë sisters died of TB at the school. One of these daughters later became a school mistress, the other a governess who married a vicar in Canada; another daughter married the vicar of Cleeve Prior, Worcestershire.

One of the sons used his clergy education to become a teacher of the classics. Two others became clergymen, one having started in engineering. Another son founded an Augustine Mission in Fulham, became Canon of Madras Cathedral in India, and ended up as vicar of Whittlebury-cum-Silverstone in Northamptonshire. Our Charles Edward became a commercial clerk – more of him next week.

If you prefer preachers of the ‘hellfire and damnation’ variety, we have them too. Daniel Lambert (whose grandson married Charles Edward’s granddaughter) had a sister Jane. While Daniel taught at a British school, for pupils of “every Religious Persuasion”, Jane taught at a rival National School, which stressed Anglican religious education.

She was also a lay preacher, and in 1876 in Shropshire, she married a Primitive Methodist minister. “As a preacher, [he] belonged to the evangelical school, preaching a full, free, and present salvation; his sermons were carefully prepared and forcefully delivered.” I found them in Buckingham in the 1901 census, and realised that I’d photo’d his chapel, unaware of any connexion. Then I found a list of his former postings, and that I’d photo’d his chapel at Oswestry too.